Erich Alfred Hartmann was a Geman fighter pilot. Not only did he fly 1,404 combat missions, but he was also the most successful fighter ace 🔗 of World War II. Here’s his story and the medals he was awarded for his actions.

Who Was Erich Alfred Hartmann?

Erich Alfred Hartmann was born on 19 April 1922 in Weissach, Württemberg, Germany. He spent his childhood in China because his father had to work there after the economic depression that followed World War I. When the Chinese Civil War erupted in 1928, the family had to return to Germany.

Hartmann attended Volksschule in Weil im Schönbuch and gymnasium in Böblingen, the National Political Institutes of Education in Rottweil, and Korntal, where he obtained his Abitur. Korntal was also where Hartmann met his wife-to-be, Ursula.

His flying career began soon after when he joined the Glider training program of the fledgling Luftwaffe. In fact, he was taught to fly by his mother, Elisabeth Wilhelmine Machtholf, one of the first female gliders in the country! Although the Hartmanns had owned a light aircraft, they had been forced to sell it in 1932.

The rise to power of the Nazi Party in 1933 resulted in increased support for gliding – reason why his mother was able to open a blub in Weil im Schönbuch where she served as an instructor.

The Early Military Career of Erich Alfred Hartmann

Erich Alfred Hartmann’s military career began in 1 October 1940, when he started training with the 10th Flying Regiment in Neukuhren. He soon progressed to making his first flight as an instructor with the the Luftkriegsschule 2 (Air War School 2) in Berlin-Gatow. Hartmann then moved on to advanced flight training at pre-fighter school 2 in Lachen-Speyerdorf on 1 November 1941.

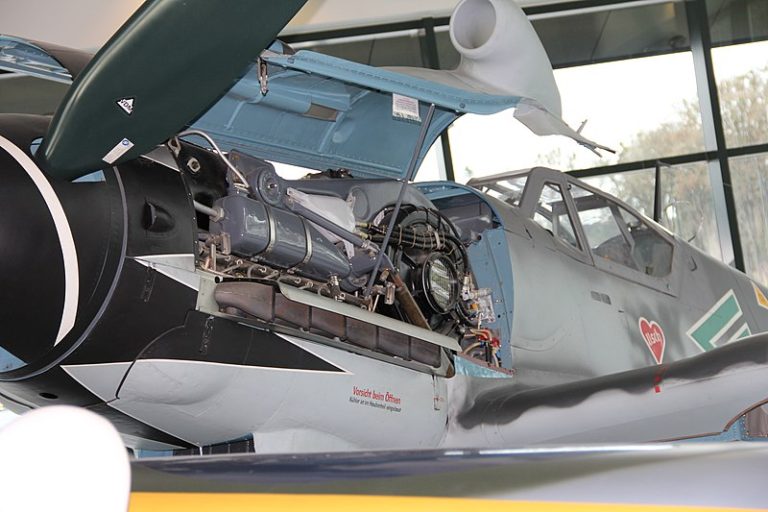

Lachen-Speyerdorf was where Hartmann learned gunnery skills and combat techniques. Between 1 March 1942 and 20 August 1942, he actually learned to fly the Messerschmitt Bf 109 🔗

Although Hartmann was a talented pilot, his training didn’t always go smoothly. In 1942, he ignored regulations to perform acrobatics using his Bf 109, which led to a week of confinement and a loss of two-thirds of his pay. Of this event, Hartmann actually said:

That week confined to my room actually saved my life. I had been scheduled to go up on a gunnery flight the afternoon that I was confined. My roommate took the flight instead of me, in an aircraft I had been scheduled to fly. Shortly after he took off, while on his way to the gunnery range, he developed engine trouble and had to crash-land near the Hindenburg-Kattowitz railroad. He was killed in the crash.

Erich Aldred Hartmann

He learned from this experience, as he later passed on his credo to younger pilots. This was the idea that you should fly with your head, not your muscles.

Erich Alfred Hartmann During World War II

Erich Alfred Hartmann’s first assignment was as pat of the wing called Jagdgeschwader 52 (or JG 52), on the Eastern Front in the Soviet Union. Although the wing was equipped with Messerschmitts Me 109s, Hartmann and other pilots were instructed with ferrying Junkers Ju 87 Stukas down to Mariupol. During his fist flight, he actually had a brake failure and crashed the Stuka, destroying the controller’s hut. He was then assigned to III Gruppe of JG 52, led by group commander Major Hubertus von Bonin. During this time, he flew with experienced pilots such as Hans Dammers, Josef Zwernemann, and Alfred Grislawski (who said of Hartmann that he was a talented pilot).

Perhaps one of the reasons why Hartmann became a success had to do also with his place as wingman to Paule Roßmann, who became a sort of teacher to him. with the help of these other pilots, Hartmann soon adopted the tactic “See – Decide – Attack – Break,” which had originated from Roßmann’s solution to being injured in one arm (“Stand off, evaluate the situation, select a target that was not taking evasive action, and destroy it at close range).

Erich Alfred Hartmann's Fighting Techniques

Hartmann was a master of stalk-and-ambush tactics. This meant that he preferred to ambush and fire at close range instead of dogfighting his enemies. When asked about his victories, Hartmann frequently explained that, along with firing at close range, Soviet maneuvers and defensive armament were inadequate, too.

Here are some of the things that characterized Erich Alfred Hartmann’s method of attack:

- Hold fire until the enemy aircraft is extremely close (20 meters/66 feet or less).

- When attacking, unleash a short burst at point blank.

Additionally, Hartmann would also:

- Only reveal his position at the last minute.

- Compensate for low muzzle velocity by using higher ones (for exampe, those of the Bf 109 model).

- Shoot accurately and use less ammunition.

- Prevent the adversary from making evasive maneuvers.

Once Hartmann got the kill, he immediately vacated the area. Survival was paramount, as another pilot could re-enter the zone and have combat advantage.

Hartmann's Fighter Ace Victories - The Total Count

Erich Alfred Hartmann survived 1,400 missiles over the course of the Second World War. In total, he’s believed to have downed 352 allied aircraft (mostly Soviet, but also American). This makes him the most successful fighter ace in history.

His ability to take on enemy aircraft was so effective, it’s said many Soviet pilots evaded his plane as soon as they would recognize the black tulip he had gotten painted on his aircraft. They’d rather retreat back to their base than face the ace.

Hartmann's Karaya 1 and Black Tulip

Hartmann used a scheme in the shape of a black tulip on the engine cowling. Soon, Soviet pilots became familiar with both the symbol of the black tulip he had flown on a few occasions and his radio call sign of Karaya 1, and put a price of 10,000 rubles on his head. An interesting fact is that, because many pilots didn’t want to face Hartmann, the Germans would allocate his plane to novices because they could fly it in relative safety.

Hartmann had the tulip removed on 21 March 1944, after his kill rate dropped due to the reluctance of Soviet pilots. With the symbol gone, his aircraft claimed over 50 victories in the following two months.

Erich Alfred Hartmann's Military Medals

Erich Alfred Hartmann received multiple medals during his career. The first one was the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross (or Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes in German), which was awarded to him on 29 October 1943. After passing the 3000mark on 24 August 1044, Hartmann was summoned to the “Wolf’s Lair” (Führerhauptquartier Wolfsschanze), Adolf Hitler’s military headquarters close to Rastenburg, where he was awarded the Diamonds to the Knight’s Cross. Other medals given to Hartmann include the Front Flying Clasp of the Luftwaffe in Gold with Pennant “1300”, the Pilot/Observer Badge in Gold with Diamonds, the Eastern Front Medal, the Iron Cross (2nd and 1st class), the Honour Goblet of the Luftwaffe, the German Cross in Gold, and the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds.

The Pilot / Observer Badge of the Luftwaffe

The Pilot/Observer Badge (or Flugzeugführer- und Beobachterabzeichen in German) was a WW2 German decoration instituted by Hermann Göring.

The Eastern Front Medal Winterschlacht im Osten

The Eastern Front Medal was a World War II German military decoration awarded to those who served during the winter campaign.

The Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross (EK 1939)

The Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross was the highest military and paramilitary award for the forces of Nazi Germany during World War II.

The German Cross (Nazi-Germany)

The German Cross (Deutsches Kreuz) was instituted by Adolf Hitler on 28 September 1941 and awarded in gold and silver.