Did you know that the most decorated woman of World War II was a spy? That’s right. Her name was Odette Sansom, a woman who was originally born in France and later moved to Britain, married an Englishman, and had three girls.

Odette would survive several years in prison after being captured by the Germans before the war ended. She was a determined, audacious woman whose adventurous and loyal spirit made her one of Britain’s best spies. Odette, better known by her code name of Lise, was also World War II’s most highly decorated spy.

Who Was Odette Sansom?

Odette Marie Céline was born on April 28, 1912 to Gaston and Yvonne Brailly who lived in Amiens, France. Her brother Louis was born a year later in 1913. In 1914 when World War I broke out, Odette’s father joined the Infantry Regiment and received the Croix de Guerre and Médaille Militaire for his bravery. He died trying to find two of his men who had gone missing after the Battle of Verdun. Thus, Odette and her brother Louis grew up never knowing their father except his brave deeds.

Odette was a sickly child, but she managed to grow out of that when her mother enrolled her at a convent near the English Channel. When Odette graduated from high school, the nuns wrote in their final report that Odette was intelligent but also petulant. This streak would be seen clearly in Odette’s later activities as a spy.

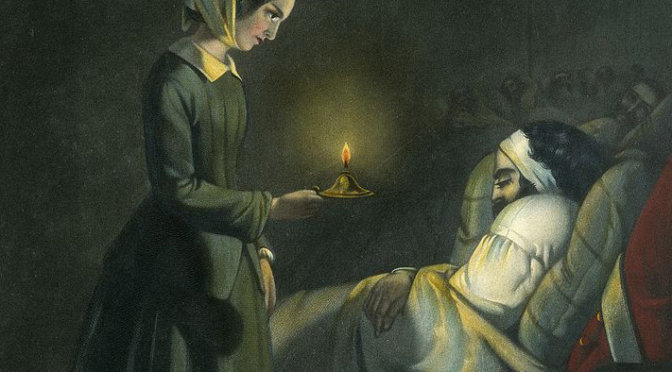

Bessie Dora Bowhill was a woman who served alongside of Dr. Inglis. Although Bowhill is less well-known than Inglis, she nevertheless did much to improve the lives of the Serbians she served. Bowhill had served during the Boer War and joined one of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals in Serbia during the First World War. She retained her senior position as a matron of the unit until she left Serbia in 1916. Like Dr. Inglis, Bowhill experienced the German occupation and did much to assist the suffering Serbians. Bowhill received the Serbian Cross of Mercy as well as the British War Medal and the British Victory Medal due to her nursing work in Serbia.

Odette married an Englishman, Roy Sansom, in 1930, and they moved to London after the birth of their first daughter, Francoise, 1932. They would later have Lily in 1934 and Marianne in 1936. After Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939 and France and Britain declared war, Roy enlisted with the British army and Odette was left at home to take care of their girls.

In 1942, Odette happened to hear on the radio that the Royal Navy was asking for photos of France. Odette had spent a fair amount of time on the beaches around Calais with her brother when Odette was in high school, so she had photos to send. In addition, Odette also mentioned in an accompanying letter that her parents were French and she was well-acquainted with the coastal regions, and promptly (and mistakenly!) sent the letter to the War Office.

Odette Sansom Turns Into Lise

Around a week later, Odette was summoned to the War Office where a Major Guthrie asked if she might be interested in some part-time work. Shortly thereafter, she received a letter from Captain Selwyn Jepson, who Odette would later discover worked for the F (France) Section of the SOE—Special Operations Executive—a secret organization that was supposed to assist with resistance efforts in Nazi-occupied countries and perform acts of sabotage in those countries.

Captain Jepson asked if she would be willing to undergo training to see if she would be fit for the role of saboteur. That day and for weeks later, Odette said no, saying that she had to take care of her children. Finally, she relented, just to prove Captain Jepson wrong that she was not fit for the job. But ironically, it turned out that she was, and Odette loved the training and was propelled by her desire to assist those in France.

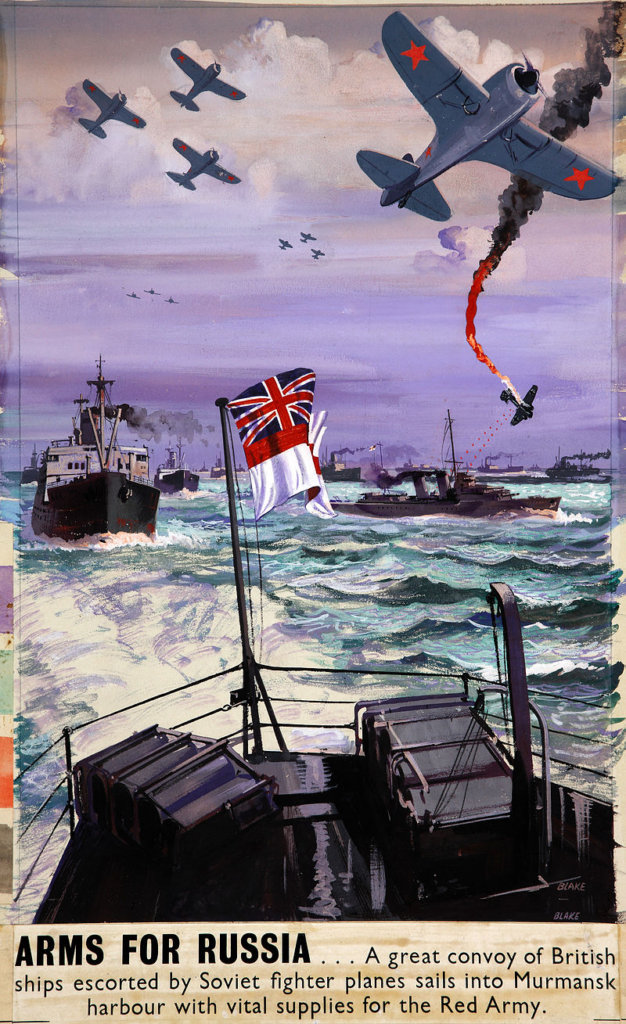

After several failed attempts to get her to France, Odette under the code name Lise, arrived in Cannes on October 1942 to temporarily join Peter Churchill, who had the code name Pierre Chauvet, Michel, or Raoul, and the SPINDLE circuit. Odette was later supposed to go on to Auxerre to establish a safe house, but Peter—unrelated to Winston Churchill—pulled some strings, and Odette joined his circuit, which included one of the best radio operators, Adolphe Rabinovitch who had the code name Arnaud.

Odette Sansom and Peter Churchill Are Captured

For six months, Odette, Peter, Arnaud, and the SPINDLE circuit together incited mayhem and avoided Germans, which required relocating several times. Unfortunately, though, a member of their network, Andre Marsac, had been captured and a sweet-talking Abwehr—the German intelligence organization—officer Hugo Bleicher, known as Colonel Henri, convinced Marsac to name members of his organization. On April 16, 1943, Odette and Peter were captured, and by this time, had developed a romantic connection so it was fairly easy to play that they were married.

From that point on until the end of the war, Odette and Peter would move into different prisons and concentration camps, sometimes together, but other times not. Odette tried to save Peter by convincing the Gestapo that she was the mastermind, not Peter, and she mentioned that Peter, who she called her husband, was the nephew of the Prime Minister Winston Churchill. These intelligent acts certainly saved Odette and Peter’s lives for some time.

Odette Sansom’s Medals:

The Gestapo brutally tortured Odette since they considered her the mastermind and asked her for the location of some individuals which only Odette knew. Even when a red hot poker was placed on her back and all of her toenails were pulled out, Odette simply replied, “I have nothing to say.”

In July 1944, Odette was sent to Ravensbruck concentration camp and was kept in a dark bunker completely isolated for three months and 11 days at one point during her stay. Even though she was extremely emaciated and her hair and teeth were falling out, Odette still had her wits about her.

The camp commandment Fritz Suhren decided to take Odette with him to the American forces in May 1945, knowing that the Allies had entered Germany and that Odette had said that she was related to Winston Churchill. Odette, however, told the Americans to take him prisoner. Although Suhren would escape several times, he was eventually hanged for war crimes due in part to Odette’s testimony.

On August 19, 1946, Odette received news that she had received the George Cross, Britain’s second-highest honor, and it was decided that she and Peter would receive their British awards together at the investiture on November 17 of that same year. The only woman out of about 250 soldiers and officers about to be decorated, Odette was given the honor of leading the investiture.

Odette’s George Cross Citation:

‘The KING has been graciously pleased to award the GEORGE CROSS to: Odette Marie Celina, Mrs. SANSOM, M.B.E., Women’s Transport Service (First Aid Nursing Yeomanry).

Mrs. Sansom was infiltrated into enemy occupied France and worked with great courage and distinction until April, 1943, when she was arrested with her Commanding Officer. Between Marseilles and Paris on the way to the prison at Fresnes, she succeeded in speaking to her Commanding Officer and for mutual protection they agreed to maintain that they were married. She adhered to this story and even succeeded in convincing her captors in spite of considerable contrary evidence and through at least fourteen interrogations. She also drew Gestapo attention from her Commanding Officer on to herself saying that he had only come to France on her insistence. She took full responsibility and agreed that it should be herself and not her Commanding Officer who should be shot. By this action she caused the Gestapo to cease paying attention to her Commanding Officer after only two interrogations. In addition the Gestapo were most determined to discover the whereabouts of a wireless operator and of another British officer whose lives were of the greatest value to the Resistance Organisation. Mrs. Sansom was the only person who knew of their whereabouts. The Gestapo tortured her most brutally to try to make her give away this information. They seared her back with a red hot iron and, when, that failed, they pulled out all her toe-nails. Mrs. Sansom, however, continually refused to speak and by her bravery and determination, she not only saved the lives of the two officers but also enabled them to carry on their most valuable work. During the period of over two years in which she was in enemy hands, she displayed courage, endurance and self-sacrifice of the highest possible order.’

The Reunion of Odette and Peter

After the war, Odette and Peter reunited after fifteen months of being separated and were married on February 15, 1947 although they would later divorce in 1956, but Peter never spoke ill of his ex-wife who married Geoffrey Hallowes later in 1956. Odette died on March 13, 1995 at the age of 82.

One of only three F Section agents operating in France to receive the George Cross, Britain’s second-highest honor, Odette was the only one to receive the award in her lifetime. In addition, Odette was the second SOE agent and the first female who had faced the enemy to receive the award. Odette did not like being especially singled out and asked that the award be regarded as acknowledgement of all who had assisted to liberate France. Even though some individuals disputed Odette’s receipt of the George Cross and asked it to be revoked, Prime Minister Macmillan refused to entertain the idea, as Odette had duly received the award.

In addition to the George Cross, Odette received the Order of the British Empire (M.B.E.), the Chevalier de la Legion d’honneur, the the 1939-1945 Star, the France and Germany Star, the War Medal 1939-1945, the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal, and the Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee Medal. In 1950, Odette’s story was made in a film called Odette, and the Royal Mail released a stamp in Odette’s honor in 2012.

Sources

- https://www.thegazette.co.uk/all-notices/content/100273

- Loftis, Larry. Code Name: Lise: The True Story of the Woman Who Became WWII’s Most Highly Decorated Spy. Gallery Books, 2019.

Guest Contributor: Rachel Basinger is a former history teacher turned freelance writer and editor. She loves studying military history, especially the World Wars, and of course military medals. She has authored three history books for young adults and transcribed interviews of World War II veterans. In her free time, Rachel is a voracious reader and is a runner who completed her first half marathon in May 2019.