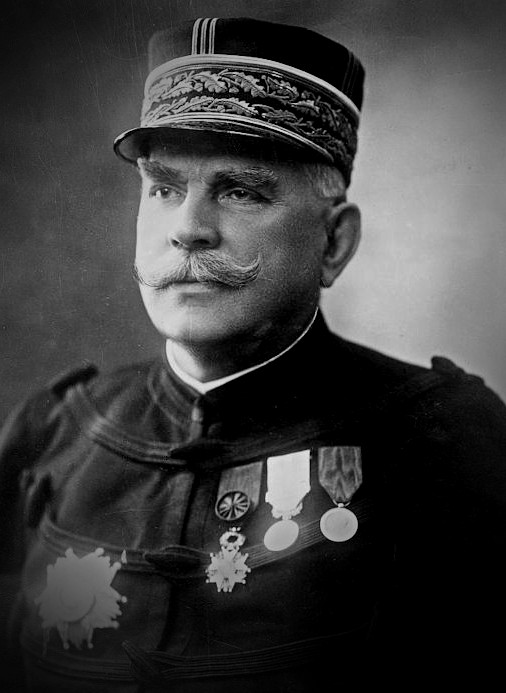

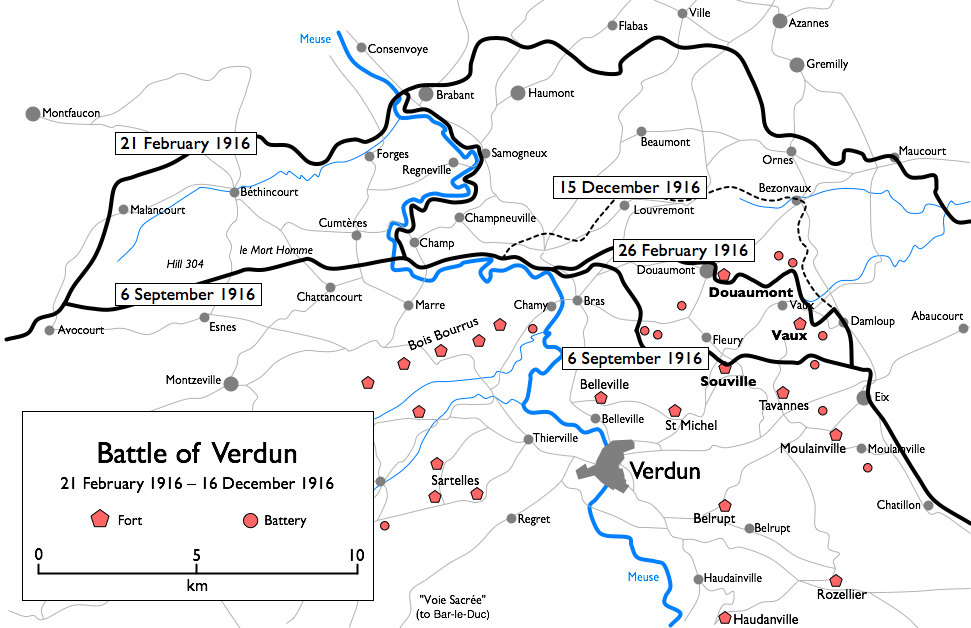

World War I has just ended. France is victorious but at a great cost. Millions of Frenchmen have died in the war, the Spanish Flu is destroying the country, and political agitation in Germany is scaring the French Government. A “Defense Council” is formed with Marshal Petain, Marshal Joffre, and Marshal Foch, the French Minister of War and the French President in the late 1910’s.

It was decided that France was no match with Germany’s demography and industry, and that it was necessary for France to defend its frontiers. Was it a good decision to focus on a defensive, rather than an offensive, strategy? Marshal Petain was strongly against it, stating that France should focus on a Maneuvering Army and not a Static one.

The Frontiers of France

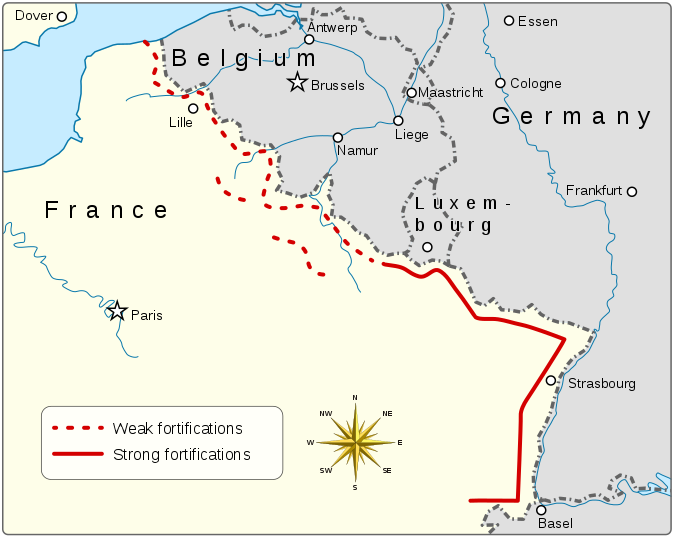

The French government decided to enact a law that would initiate the construction of a defensive line on the frontiers of France, near Switzerland and Belgium. The former had been neutral since 1815, and the latter was an ally of France. André Maginot, Minister of War in 1929, pushed hard for this law, and thus gave his name to what would later become the Maginot Line.

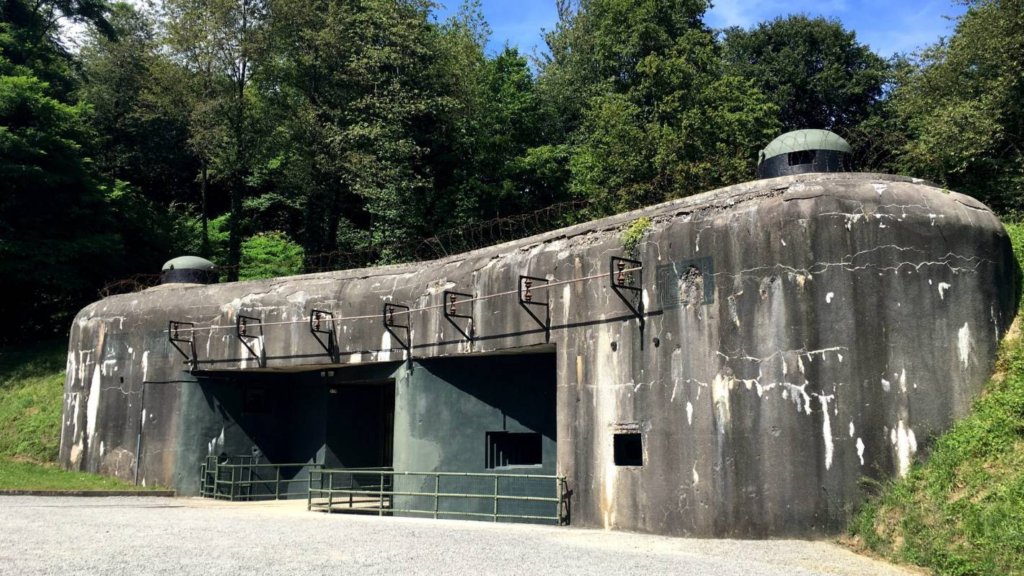

The Maginot Line was not a defensive line just at the German frontier, as the first Bunkers were built in Nice at the Italian Frontier in southeast France. Italy was no more a friend to France, and Benito Mussolini was increasingly more aggressive towards Savoie and the Nice territory. You can even find a lot of these bunkers in the Alps and get in if you dare to!

As the Occupation of the Rhineland was coming to an end in 1930, the French government decided to take the initiative by starting to build the defensive line at the German frontier in 1929. Until 1935, the German Frontier saw the acquisition of increasingly more defensive positions, artillery nests, bunkers, and tank traps.

How was the Maginot Line designed?

As you previously guessed, yes, the Maginot Line was a series of defensive position along the frontiers of France, some more armored than others and some more protected by terrain (the Alps is a fantastic wall, and Italy would never cross them in 1940).

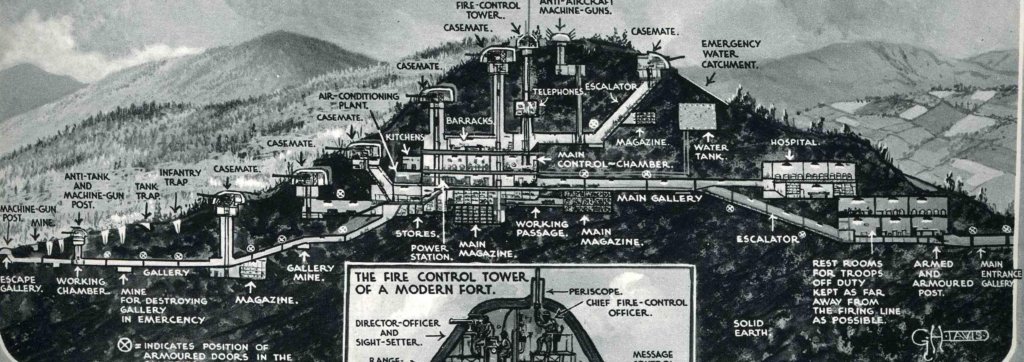

The following description applies specifically for the German border. The structure of the line was very simple yet proved to be both great and really bad. The Line was divided in 4 different ones.

The first one was the weakest one, being a simple series of outposts with sentries, barbed wires, and mines. It was designed in a way that the sentries could quickly alert the second line that danger was coming. The barbed wires spread a distance of 10 to 15 meters. This was plenty for the machine guns from the second line to shoot down anything that could move in this zone as the French machine guns could shoot up to 1,200 meters.

The second line was the strongest one. Full of bunkers, more barbed wires, and mines, it was located around two kilometers behind the front line. With tank traps and machine gun nests located under heavy artillery cover, it was designed not only to hold, but also to inflict heavy casualties to the enemies.

The third line was designed to provide cover to the fighting troops in the field. With machine gun nests and bunkers, this line was designed to hold the enemy if it got through the first two lines through close quarter combat.

The fourth and last line was the logistic line: barracks, ammunition, and artillery. It was designed to provide support only. The enemy was not supposed to reach it and never really did.

The main goal of the Maginot Line was to inflict major casualties and to experience as few casualties as possible. The French demography was in no match for the German demography, and French blood had to be spared as much as possible.

The Maginot Line had a political goal too, as it was designed in a way to make the Germans attack through Belgium. Since the United Kingdom had guaranteed the independence of Belgium, if Germany dared to attack Belgium again, then the British would declare war to Germany again. But the French Government was then sure that Germany would never dare touch Belgium again.

This looked great but as General Patton said…

“There is no such things as successful defense.”

The defensive lines, even designed with extreme caution, had flaws. One of them is that, as you will see later on, there was no escape for some bunkers. Soldiers were trapped in shelters, cut from reinforcements and fresh air.

But the biggest flaw was that the line was incomplete because of diplomacy. To maintain a good relationship with its neutral neighbors of Belgium and Switzerland, the line at the borders of these two countries were lightly defended. It was a diplomatic strategy, but it proved to be an enormous mistake. Why? Not only because Germany did something that the French High Command did not really expect, but even worse, the line was designed in a way to defend the border and forbid the crossing of it. The back of the line was thus very vulnerable if a flanking attack happened and took the line from behind.

“Peace for our time…”

From 1936 to 1939, the line was fully occupied for different reasons and different lengths: the Rhineland re-militarization in ’36, the Anschluss, and the Sudeten crisis in ’38.

The Sudeten crisis had a major impact on the line. Political? Maybe. Strategic? No more than being a different crisis until the breakout of the war. For the Maginot Line itself, it was a disaster. When Germany annexed the Sudetenland, the Czech fortifications were thus captured and, as they were built with the help of French engineers, the Wehrmacht tested the fortifications and figured out how to break them. A few years later, this would prove to be a disaster for France.

The Phony War

Poland had just rejected Germany’s demand about the Danzig corridor. War would breakout in a matter of time. The 21st of August 1939, France decided to mobilize and thus garrison the fortifications. Total mobilization would start on the 2nd of September, and war between Germany and France would start the 3rd after France declared war. During the first days of the war, nothing would happen. Besides some artillery shots, nothing. The Sarre offensive would do nothing as well.

Soon the phony war started. During winter of 1939-1940, the fortifications would continue to grow until May 1940. Did the French High Command ever expect what would follow?

“Fall Gleb”

It is the 10th of May 1940. Nothing changes as the Phony War continues. There are no casualties, and the soldiers are waiting. Waiting for what? Are they expecting anything? No. The French High Command has its “wall,” and the Army is believes that the enemies will not attack through it. They think that even attempting it would be a suicide mission.

The Wehrmacht has an other idea.

The Fall Gleb plan consisted of cutting through the Netherlands and Belgium and Luxemburg, bypassing the strongest elements of the Maginot Line. The French High Command didn’t really expect that. Even worse, they didn’t expect Germany to pierce the front in the Ardennes range and its deep forest. The Germans met some fortifications of the Maginot Line but they were only lightly defended as it was so unthinkable to attack through the Ardennes. What the Germans did was pretty simple. They basically dodged the strongest line of defense and attacked where it was weak. Punching hard in the Ardennes and in the direction of Sedan, like in 1870, the French High Command realized a disaster was happening.

The worse was yet to come as “Plan Dyle” started as a response to the German attack. The Allies entered in Belgium with the desire to counter-attack the Germans. A disaster happened during the following days through the application of the plan. The Germans were attacking deeper and deeper behind the Allies, and they were now flanking them. The Wehrmacht then attacked and pushed to the Channel and encircled most of the Allied armies in Belgium. Most of the French Armies, the British Corps, and the Belgian army began to surrender, completely cut off from the back. The Maginot Line saw little to no action. Most of the fortifications the Germans ran into were so lightly defended that it was impossible for the French troops to hold any attack there. Most of them were captured with small confrontation since the Germans were so dominant in every way. Some forts fought hard though. A strange case happened too with a fortification that would prove to be a major flaw for the Maginot Line. A bunker was isolated and couldn’t retreat and would not surrender. It was attacked, and trapped in the bunkers the soldiers were attacked by engineers. Trapped and with no fresh air, they all suffocated.

Later on, during the “Fall Rot,” it would happen many times.

“Fall Rot,” or the End of the Battle of France

For a short period of time from the 25th of May until early June, the front was stabilizing and even with the loss of thousands of soldiers encircled and trapped in Belgium, the French dug behind the Aisne and the Somme rivers, and nothing happened for a few days. The Germans then launched their final battle plan, Fall Rot, which finally made France surrender.

During this final plan, the Germans attacked through the rivers and the strongest fortifications of the Maginot Line. Heroic defense from the French during 15 days would push back the Germans but the line would finally be breached on the 19th of June and then during the last 3 days of the Battle of France. The Latiremont Sector would fire up to 1577 shells a day to push back the assault groups, and even with the help of the “Big Bertha” and the Skoda Artillery Guns (305 mm), the line would hold in most of the fortifications.

The main danger would finally come from the back of the line, as General Heinz Guderian would push his panzers far behind the defensive line and encircle the French, too.

On the 22nd of June, the French Army would finally surrender to Germany, completely destroyed.

What about the Alps Front?

The Maginot Line was weaker there, but the Mountains were a fantastic defensive position for the French as the Germans or Italians would never break through. The Italians declared war the 10th in a very unfavorable terrain, and it proved to be a disaster. Only the German Armistice forced the French to surrender to Italy on the 25th of June.

There is also a very “internet famous” battle that happened during this short period. The “Battle of the Pont-Saint-Louis” gained fame, when 9 French soldiers held an enormous Italian attack, killing more than 150 Italians and only having two slightly injured soldiers.

Conclusion

The Maginot Line wasn’t so much of a bad idea in itself. It proved to be reliable, and it never really fell. Its only problem was that it was 30 years late. War changed during peace time, and the French stayed with the World War 1 strategies, which proved to be a total disaster. The war was now moving at a very fast pace.

The Blitzkrieg and the encirclement maneuvers of the Germans were very simple, and, in the end, not that well thought out. Their success was great but only because the French strategy was simply not possible during World War 2.

Guest Contributor: Kjetil Vion is a writer and a history enthusiast. A passionate of France and modern military history, he has a special interest into the Prussian state, specially since the Sadowa battle against Austria. Always wanting to learn more, he now looks to spread his knowledge in history.