As Joachim Von Ribbentrop and Vyacheslav Molotov signed the infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, linking Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, Europe was split into two. This Pact created two spheres of influence that the Nazis and the Communists would dominate after World War II.

Finland had never had normal relations with the Soviet Union. As this poor country broke free from the Tsardom of Russia and saw a political revolution ensuring the victory of the “Whites” against the Finnish Bolsheviks, it became the target of the Soviet Union.

Operation Barbarossa and Stalin

When you look back at the events of 1941 and Operation Barbarossa, it is easy to understand why the Soviets were so aggressive towards Finland during the 1930s, and why it ultimately led to war. Joseph Stalin said: “We can not move Leningrad back from the frontier, so we will have to push back the Frontier“.

Finland and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact in 1932 and negotiations took place between the two countries to normalize their relationship and to reassure Stalin about his frontiers, the Finnish one being a possible theater of war since the Finnish government (and Finnish socialists too) was so anti-bolshevik.

The ultimate negotiations in November 1939 were nearly done but the Finns refused to lease the Hanko Harbour for 30 years, and so, they ultimately failed. The fate was sealed and war was thus inevitable.

The beginning of a disaster

The 28th of November 1939, a false flag attack was carried by the Soviet Union. They attacked one of their own village near the Finnish border with artillery shots and killed 4 of their own soldiers. Moscow thus immediately asked for excuses from the Finnish Government, and as they refused to excuse themselves, war broke out the 1st of December 1939. The Winter War had started.

The Soviet tactic was not a well thought one. They decided to attack in waves, but the terrain wasn’t the best for it. It proved to be absolutely disastrous when performed in forests – which covers most of Finland and its borders.

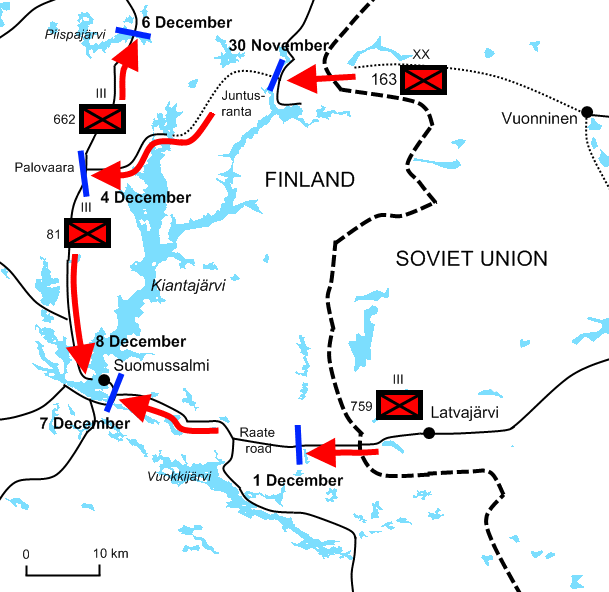

In Suomussalmi, not too far north but of strategic importance, the Soviet attack was a catastrophe. The original Soviet plan was to punch through the town and the Region, then to cut off Finland in two at Oulu at the Bothnia gulf coast. With its country split into two, it could be impossible for Finland to keep fighting and it would have been a fantastic victory for Stalin and the Soviet Union.

But something was not being accounted for: the sisu. The Sisu is a concept of hard determination, bravery, resilience. The Finns would have rather all died than let their country becoming a Soviet satellite state.

As the Soviets decided to attack to Oulu, the Finnish only had one battalion located outside Suomussalmi, at Raate. That was only one battalion to face enormous enemy forces, around 45 to 55,000 Soviets.

On December 7th, the Battle started. Suomussalmi was easily taken by the Soviets but in their retreat, the Finnish practiced the tactic that later saved the Soviet Union in 1941, the scorched-earth. The Winter War was exceptional because of the extreme temperatures the troops had to face during winter 1939-1940.

The very first day of the offensive was a victory. The following days would lead from disaster to shipwrecks. On Decembre 8th, the Soviets kept attacking through the lakes west of Suomussalmi but they never managed to break through the Finnish defensive line. The next offensives would prove to be even more and more disastrous. They also tried to attack farther north-west but it failed completely too. As the Soviet morale was sinking in the bottom of the lakes surrounding Suomussalmi, the Finnish were reinforced by a fresh battalion, led by intrepid Col. Hjalmar Siilasvuo. The initiative was not on the Soviet side anymore. Low morale, heavy casualties, failing tactics, equipment shortage, disaster was looming the soldiers of the Red Army.

Reinforced the 9th, Siilasvuo reorganized the units and went on the attack to recapture Suomussalmi, which proved to be a pyrrhic victory. The Soviets would not budge from the town and the Finnish would suffer (relatively) heavy casualties. The Soviets had bad tactics, but their art of defense would prove later to be a problem for Nazi Germany in Operation Barbarossa.

In Modern Warfare, mobility is the key and the Soviets with their heavy equipment and their tanks would try to push farther and farther in Finland but would stick to the roads. The objective to cut Finland in half, rushing to Oulu has made no sense since the region they had to cross was a forest. A giant one. As the Soviets were getting stuck on the roads and would progress very slowly, the Finnish would start attacking them, day and night.

Their mobility with the skis was the key to victory. They would harass the Soviet divisions and finally cut them off from reinforcements. Most of the 45 to 55,000 men were then totally encircled with no shelter and no equipment.

The end of the 163rd Division

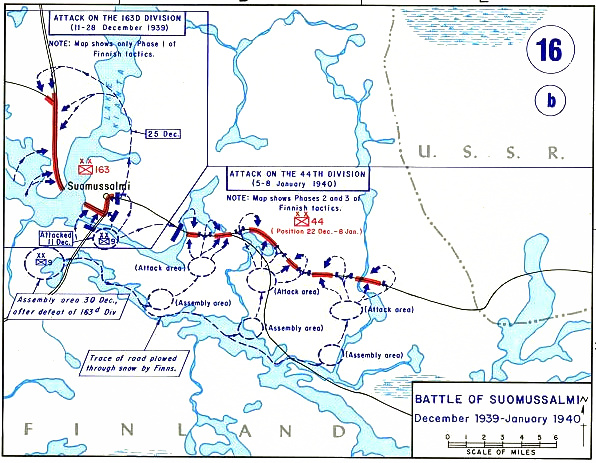

The legendary Motti tactics then happened. Motti is very simple: You have to cut the enemy into different parts and encircle them. You then have two choices, either you can assault frontally and destroy the enemy pocket or you can let the Motti “cook” itself and wait for the enemy to starve and die by himself. On the 26th, most of the enemy forces were encircled and most of them were starting to die or surrender.

On the 27th, the Finnish would finally retake Suomussalmi.

This was the end of the Battle of Suomussalmi. The casualties for the Finnish were high if you consider their very low manpower, as they lost 900 men. But in comparison with the Soviet casualties, they were inexistent. On the ~50,000 men the Soviets engaged in the Battle, half of them were killed in action or missing in action, so at least 25,000 casualties.

One battle leads to another…

The consequences following the end of the Battle were immediate and harsh for the Soviets. The 163rd Division was destroyed and the 44th Division, trailing by a few kilometers was the next target of the Finnish, on the Raate Road. 12 kilometers east of Suomussalmi, the 44th was waiting for orders from its General, Alexeï Vinogradov. Unfortunately, for them, the 44th was the target of attacks from all the available battalions from the Finnish side and this battle was even more costly than the one that took place only a few days before.

Starting the 5th and ending on the 7th, the 3,600 Finnish faced around 25,000 Soviets. It is estimated that more than 17,500 Soviets were killed or missing in action following these three days of hell. Vinogradov was held guilty by the High Command for not retreating fast enough from this tornado and was sentenced to death, and executed officially for losing 56 cantinas to the Finnish.

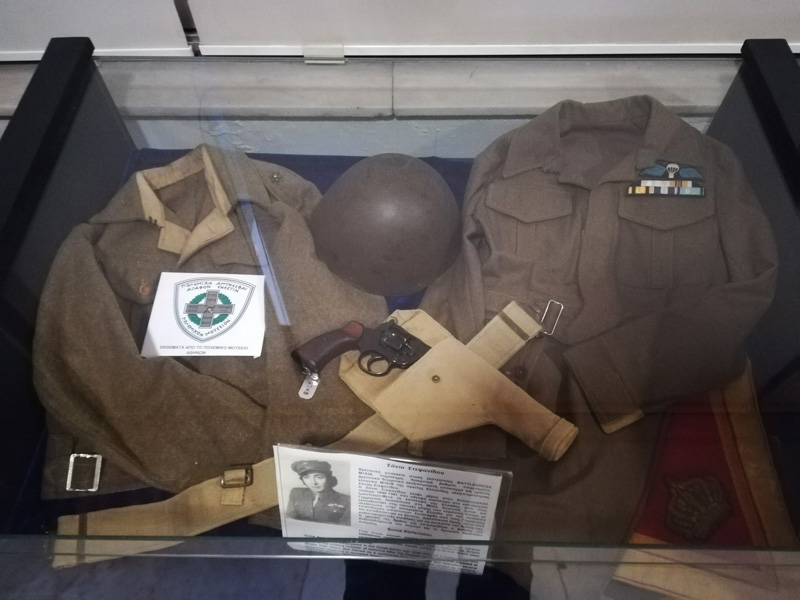

The Winter War 1939-1940 Medal and the Suomussalmi Battle Clasp

Those who took part in this slaughter on the Finnish side all received a medal: The Winter War 1939-1940 Medal. The Suomussalmi battle clasp was awarded to those who had barely a chance of winning the battle. Facing enormous mechanized troops from the East, they all deserved to get this award.

This medal, awarded in august 1940 was very simple. A black and red ribbon linked with a blackened iron plate with “Kunnia Isänmaa” inscribed on it, which could be translated as “Motherland“.

The criteria for the award of this medal was as follows: The medal was ‘established to commemorate the war of 1939–1940 and the unanimous will to defend it and the deeds done for the benefit of the motherland.’ The medal was generally very liberally granted to those engaged in some form of war work. This could range from those who cooked and baked in canteens to soldiers and young boys and girls who helped pass messages and washed uniforms.

Conclusion

Little Finland had no chance had the beginning of the War and nobody expected them to hold for such a long time. For a few months, the Finnish destroyed divisions, tanks, planes all day long. This performance was absolutely stunning but in the end, even with their heroic defense, they couldn’t hold forever.

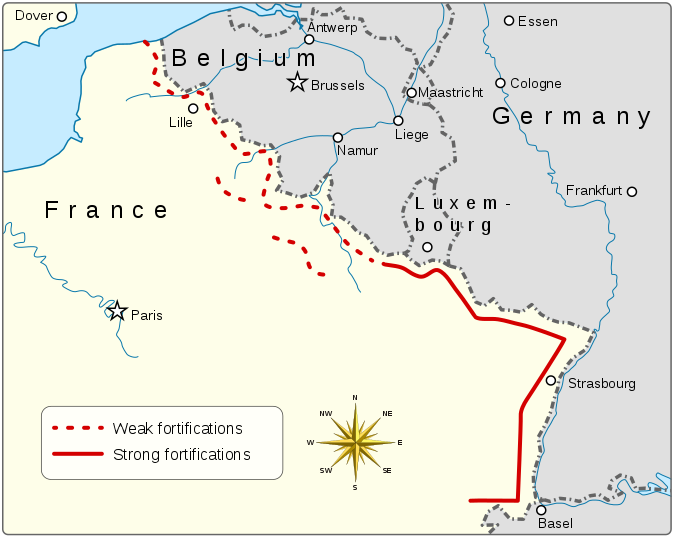

In late February, the situation was pretty clear: the Mannerheim line was breached in the South and, the Soviets were starting to push hard through Finland. The end of the war was near and, the Soviets searched for an armistice.

Even though some people may argue that the Soviets lost the war, I believe they are mostly wrong. Since the Soviets obtained even more then what they asked before the breakout of the war, they are victorious, but at a terrible price. This war served as a good lesson for the Soviets and what they saw in Suomussalmi and the scorched-earth tactic would be later employed in Belarus and Ukraine to slow the German advance in Operation Barbarossa.

We can all wonder what would have happened to Finland if the Soviets had cut them off in two. But thanks for to the defenders of Suomussalmi and the sacrifice, nobody knows it. They played a major role in this war and would be of great help when negotiations set off between Finland and the Soviet Union.

This battle, and many others, would shine all over the world and the Finnish would always be seen as a harsh warrior.

Guest Contributor: Kjetil Vion is a writer and a history enthusiast. A passionate of France and modern military history, he has a special interest into the Prussian state, specially since the Sadowa battle against Austria. Always wanting to learn more, he now looks to spread his knowledge in history.